talks about Charlottesville, Austin, the Music Biz, etc.

It should be noted here that without Danny Schmidt, there would be no focus on Charlottesville here at rockandreprise.net, no rundown on that town's vibrant music scene, no inclusion of Charlottesville in this website's envisioned pieces about the independents' roles in a chaotic and morphing-before-our-very-eyes music industry. Originally, Danny Schmidt himself was to be the center of just one article, a look behind the musician and at his music. A handful of rebuffs by Danny put that idea to rest and after suggestions at every turn to write about the entire Charlottesville music scene and not just his small part, we acquiesced. On May 15th of 2008, while driving the freeways between Austin, where he now lives, and Dallas, Danny schooled us on a handful of subjects so well that what started out to be an informal Schmidt bio will now grace these pages in interview form because, as you will discover, some conversations are best presented as just that and paraphrasing just will not do. Here are Danny's thoughts and words, edited only to protect the innocent and to make Danny sound a lot smarter than he really is. And Danny? I'm only running this after the check clears.

R&R: What I need from you is the basic Danny Schmidt story, such as where you were when you decided to be a musician and how long it took before you could actually support yourself as such...

Danny: Well, I've been playing guitar since I was about thirteen, just as a closet picker. I didn't play with anyone then or anything like that, but I played a lot.

R&R: How old are you now?

Danny: Thirty-seven. I was living on a communal farm in Virginia. I left school to go live in a commune in the Ozarks called the East Wind Community, then left East Wind to live in a place called Twin Oaks Community, out in central Virginia, about a half hour from Charlottesville. I was about 25 and that was when I started writing songs. Because I fell in love with a girl. Actually, that is what drew me out to Virginia in the first place. I just started writing songs. I had not intended to or anything. I lived in that community (Twin Oaks), on that farm, for about four years. When I started writing and playing songs for some of the people in that community, they encouraged me to go out and share some of the songs with the public. By the time I made it to Charlottesville, I was 28 or 29 and that's when I started performing.

Devon (Sproule) grew up in Twin Oaks, so I've known Devon since she was 12 or 13. She was just a kid growing up on a farm. I knew her when she first started picking up the guitar. She was always really musical. By the time I decided to leave the community, she was about 16 and decided that she was going to leave the community as well and moved to town. It was coincidental that we both came to town at the same time. We both started to perform at open mikes and smaller shows. The first real open mike I went to was at a place called the Prism Coffeehouse, which doesn't exist anymore, sadly, but was at the time the second oldest running coffeehouse in the country. There were posters on the wall for, say, Emmylou Harris in 1971 for like 75 cents or something like that.

Anyway, I lucked into meeting five or six people who wanted to do more with their music. We all really clicked, so we decided to have these showcase kind of things, collaborative kinds of shows where we would all play for like 20 or 25 minutes. There would be four or five of us each time. And that is what became Acoustic Charlottesville, which turned into a monthly showcase of Charlottesville songwriters. That went on for three or four years.

R&R: This Acoustic Charlottesville is attached to the website of that name?

Danny: It eventually went like this: I started leaving town too much and some of the others started having kids, so we eventually stopped doing them. I suppose the website is still up. Some other people took it over for about two years and then they moved on too. I haven't looked at the website for a long time, but I suppose it has quite a list of performers.

R&R: Quite a long list.

Danny: That will give you some kind of idea of the amount of people we were drawing out of the woodworks to come play. Eventually, we kind of cycled ourselves out of the loop, the organizers did. One of us would play each show and maybe three or four other acts, newer ones, would comprise the rest of the show, those being pretty much within 50 miles of Charlottesville. Certain artists rotated to the top and we became good friends, so a lot of us started putting together more focused shows at a little nicer kind of venue for maybe a couple hundred people. There would be three or four of us. That was about the time Paul Curreri came to town. You know his stuff?

R&R: Only The Velvet Rut.

Danny: That is a bit of a departure for him. Most of his earlier stuff is more rooted in acoustic blues, finger-styling kind of stuff.

R&R: I was wondering about that. Most of the references I've found talked more in terms of Dave Van Ronk and the like. I didn't hear anything like that in The Velvet Rut at all. I'm still shaking my head and wondering what the hell he was doing on that one. What guitar!

Danny: Yeah, that one was more experimental and avant-garde for him. He was just fooling around with the home studio he was building and it all grew out of that.

When Paul moved to town, like on the first day, he met Devon at one of her shows and got drunk and jumped up onstage and started singing harmonies with her on a Johnny Cash song she was doing. The next day was my birthday and Devon brought Paul along to my party and by the next week, he was like best friends with my whole group of friends.

That next couple of years were real fertile years for songwriting in Charlottesville. We were all working. We did so many collaborative shows that there was always an incentive to get more stuff done, like write new songs or polish old ones up. That's about when I decided that I was going to move back home to Austin where I had grown up. I had never intended to stay in Charlottesville, but when I first left Twin Oaks and fell in with those friends, I got drawn in, and like five years later... I guess I'd been playing for about five years at that point in time and music was getting to be a more and more significant part of what I did.

R&R: What were you doing to survive?

Danny: There was a social service organization which worked with folks who were mentally handicapped. I worked at a home with five mentally challenged adults. The way shifts worked, I could get full-time in in three long days and that left me four days to do little mini-tours. It was a good way, as I was starting to branch out from Charlottesville, to do it without too much pressure on the finances. So if it was a break-even trip, that was fine. It didn't need to make me any money, which was good because when you're first starting to introduce your music to new markets, it's hard to make much money.

At the end of that five years in Charlottesville, though, I decided that I didn't want to play music anymore, professionally.

R&R: How long ago was that?

Danny: That was 2003. All my friends were musicians and they were all starting to spread their wings and start touring more and more. That's all we talked about when we were together. It was really hard for me to stay divorced from music, hanging out with all of those folks. I had never really intended to stay in Virginia. I mean, my actual family was down in Austin.

So I moved to Austin and quit playing music. I mean, I was still going to write and record, just not plan on doing it to make money. I have friends who have a video and film business there and they invited me to work with them.

Two or three months into Austin, I had a health crisis which ended up costing me thirty-five or forty thousand dollars because I had given up my insurance when I left the job in Charlottesville and I hadn't yet picked up any in Austin. I was kind of screwed and realized that my best avenue to raise that kind of money quickly was through music. Whenever I finish a new song, I record it into my home computer just so I don't forget it, so I had a whole collection of home recordings which had never been released. I announced to my email list that I was having these health problems, that I needed to raise some money, and that I was going to make these home recordings available for whatever the people felt like contributing. Then, when I was healthy again, I was going to do a house concert tour to try and raise the rest of the money, so if they were interested in doing a house concert six or nine months later, they could just shoot me an email. I got a really great response. People were really nice to me.

R&R: A lot of it out of Charlottesville?

Danny: All over, actually. At that point, I had a couple of records out and had been sending them to radio, so there was a smattering of people all around who knew my music. But obviously, my musical home base was still Charlottesville. They were great. A bunch of my musician friends organized a benefit concert at a big theater in Charlottesville. But what happened was that the whole thing managed to drag me back into the music business. By the end of that year, after I'd done the tour of house concerts to raise money, I was back into the swing of doing music as a living. And from that point on, it's been my main business.

R&R: Did you find that it was the music drawing you back, or maybe the sense of mortality?

Danny: Well, for me, the music and the music business are so separate in my mind... It was the music business I was trying to get away from. To me, the business was making it so that I didn't really like music that much. All my thoughts were about booking better shows, the next town, promoting this or that show, making sure the next tour was all in line and then the one after that was online. I was spending most of my time on the computer and little time playing my guitar. I decided that the only way to get back to the music was to ditch the business part of it. Of course, after that kind of renaissance I had with it all, I tried to strike some sort of balance. I was just going to put just so much energy into the business part, making sure I kept a positive balance of energy for the artistic part. The time off from business I took in Austin did kind of re-inspire me, artistically.

R&R: Were you suffering burnout?

Danny: Yeah. And I realized that my life was being spent at an office job. I would spend eight hours a day doing email and maybe fifteen minutes playing guitar, and that wasn't where my priorities were. Or where my values were, I guess. But that was where my time was going.

R&R: About the health thing. I assume it was lung cancer?

Danny: No.

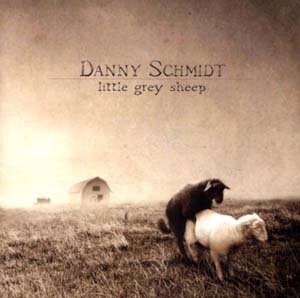

R&R: The first thought I had was lung cancer because of the first track on your last album, Little Grey Sheep, called Leaves Are Burning.

Danny: No, but the funny thing is that I started smoking again as soon as I came home from the doctor's office. I had quit for awhile.

R&R: Stress reliever?

Danny: Yeah. I decided I'd start worrying about quitting smoking again the next time.

R&R: So did you quit?

Danny: Oh, yeah. I've quit since then.

R&R: So you smoked for awhile and then quit?

Danny: I've smoked off and on since I was about nineteen. Mostly on, except for short periods of quitting.

R&R: Do you notice a difference in your voice?

Danny: Oh, yeah. A world of difference.

R&R: Is your voice clearer when you don't smoke?

Danny: Yeah, and it's just much more consistent. I don't stress out going into a show whether my voice is going to be so brittle that it will jump in unpredictable leaps. Paul's just the opposite. Paul smokes up a storm and it helps his voice. He feels like it helps him get better control over his voice, but for me, it just dries out my vocal chords to the point that they don't respond the way I expect.

R&R: What is the difference between Charlottesville and Austin, music-scene wise? Do you find it to be more inspiring in Austin or is it just the fact that it is a livelier, more accessible area to play, or what?

Danny: I actually like Charlottesville more than Austin. Of course, Austin is where my family is. I played in Charlottesville more often than I play in Austin. Austin is not a great singer/songwriter town, or it's not a great solo singer/songwriter town, odd as that sounds, relative to how good it is for other genres of music. There are a whole lot of venues where you need a band to pull it off, so most singer/songwriters here end up putting a band together. And, really, it's easy to put a band together here because there is a shitload of really talented, reasonably priced musicians who are trying to make a living in Austin. There are a couple of singer/songwriter venues, but not as many as you might expect, especially being's how much music there is.

R&R: Like you say, I would have expected a ton of venues, judging by all of the individual musicians who have come out of or have attached themselves to the area.

Danny: I know. I know. But there really aren't, surprisingly enough. In Charlottesville, for the size of it, there are some really good singer/songwriter venues. Gravity Lounge, these days, is the best. The Prism Coffeehouse just shut down recently, but that was a staple for like 35 years. Starr Hill Music Hall was good when you got a little bit bigger. Then there were some of the monthly series places, like Acoustic Muse, a solo singer/songwriter venue, and Acoustic Charlottesville, which is not running anymore but was for a long time. And there is a place just outside of town called Rapunzel's, out in Lovingston.

R&R: How core is Charlottesville to survival? How far out would you have to go if you really wanted to support yourself musically?

Danny: Well, if you're talking about supporting yourself solely off of music, I'm not sure you could do it without playing weddings and party gigs and stuff like that.

R&R: Is that what most musicians there do?

Danny: No. Most musicians go a little farther. They cast a spider web. Charlottesville is just an hour and fifteen minutes from Richmond, another decent market. It's an hour from Harrisonburg, where there is a big college. It's two hours from D.C. About three hours away, you start getting down into Southwest Virginia--- Plattsburg is down there and there are a bunch of little towns which are pretty supportive. Once you get to D.C., there is the I-95 corridor, on which you could just step another 45 minutes and get to the next big market. From there, you can get to Baltimore in an hour, Philly in another hour, and from Philly you can get to New York and New Jersey.

R&R: Is that how you did it? Just going a bit further and a bit further, branching out?

Danny: Yeah. A little less methodical than that, but that was the gist of it. I mean, when you're first starting out, you follow the leads, wherever they come from. For whatever reason, someone liked my music in Louisville, Kentucky--- some DJ up there--- so that was one of the first places I started going, even though it was a good six or seven hours away. And that was an incentive to pick steps along the way. If I could find two-hour steps on the way to Louisville, that made a nice four-day tour. But the mid-Atlantic is nicely placed. It's not too far until you're getting into North Carolina and even then, there are a number of nice places to play there. Then it's just a few hours to Atlanta. I mean, as long as the steps are not too far from each other, everything is pretty well situated. It's not like being in Texas. Right now, I'm driving to Dallas, three and a half to four hours, to get to the next decent market north of Austin.

R&R: Is your base more rural or urban?

Danny: I would say urban, but only because they have the infrastructure to hear your music. They are more likely to have a public radio station more supportive of independent music. They are more likely to have a decent weekly entertainment newspaper which will write articles about the music coming through. They are more likely to have a music series or an arts council or something like that which will sponsor a show by new artists and which will bring the music to the area.

I mean, Rapunzel's in Lovingston is just a rural little community, but they wanted to bring the music out there, so they organized themselves.

R&R: How long has Rapunzel's been around?

Danny: Six or seven years, I think.

R&R: Let's talk about this whole indie movement. Do you find that movement is becoming a bit more cohesive, or has there been no change and you're basically just growing into it, so to speak? My point being, just how much of an effect has the implosion of the music industry had on the independent musician and his or her survival?

Danny: I think it's had a large impact. It's decreased the pool of musicians who are not indie, who are getting some sort of major label support. Fewer artists are getting major label support now so labels like New West, which used to be a minor league stepping stone to the major labels for up and coming artists, are now downward stepping stones. Seldom will they sign an unknown artist now, regardless of how good they are. It just doesn't matter. Now they are signing artists like Willie Nelson, artists who are getting dropped from their labels because they don't sell the same volume anymore.

R&R: What you're saying is that the minor league labels are now stopping what they used to do and picking up major artists in lieu of the unknowns?

Danny: On their way down, yes. And booking agents and the whole infrastructure of the industry are doing the same thing. It makes sense. You have to invest so much less promotional money to tell the world about Willie Nelson's new record than you would to tell the world about Danny Schmidt's new record. Because he's had 30 years of millions of dollars being spent promoting his name. People are already interested, so it makes the booking agent's job easier and it makes the publicist's job easier. There are enough artists like that falling from the majors that the small labels can fill their rosters with those folks and not have to fool with investing in up and coming artists.

R&R: So you seriously think that this is the reason that the real indies are have so much trouble getting noticed?

Danny: Yes. Certainly. It's all a product of the fact that fewer records are being sold. So when people say stealing music hurts only the big labels, they're wrong. They don't understand the whole ecosystem. The money trickles down. If the people at the top are making less money, they're going to make sure that they make their money, regardless. They won't release the Willie Nelson record anymore because the margin on it... what they sell versus what they used to be able to sell is that much less. The margin is not high enough for them anymore. So it trickles down, and Willie Nelson has to go somewhere, you know.

That's sort of the negative story about why there are so many indie artists. The positive story is that you can do it now as an indie whereas I don't think you could have 20 years ago.

R&R: Why can you do it now as opposed to 20 years ago?

Danny: A couple of reasons. For one, you can afford to make the records yourself. The equipment is not that expensive anymore, relatively. It comes down to how good you are with your ears or how good the people you are working with are. Anybody can certainly make a record now for under ten grand, and a lot of people for under five grand, which sounds really good. That is at least ten times cheaper than it used to be, for the cheapest stuff.

There is also technology which allows you to do grass roots connecting. You know, it used to be that when somebody made a record, there would be a two or three million dollar top-down advertising campaign broadcasting that person's name to everyone, which would trickle down to the people who would be interested in it. That is how they built their audience. Nowadays, with email and stuff like that... I push my email list more than any single thing. I'd almost rather have someone sign my email list at a concert than buy an album. Because that's my pathway to reach them directly and tell them when I'm going to be in their neighborhood at a concert that might cost them ten or fifteen bucks. If they're interested, they might bring ten people and those ten people might buy fifteen CDs total over a period of time. And the one person of those ten who signs the email list might notice that next month, I have a concert in New York City, and say hey, I have a cousin in New York who writes for, say, The Village Voice, I'm going to send him out. It creates this sort of grass roots web, a network which you can reach directly for no money. You know, up until Parables and Primes, I think the total of my whole advertising budget was maybe 25 dollars, and that was for printing up posters for my CD release party. That was all the money I'd spent on the promotion of three albums.

R&R: How many albums did you have before Parables?

Danny: Three. Parables was the fourth. With Parables, I did a radio mailout, so that one cost me the price of the CDs plus packaging and a month of my time. But it's just a whole different model. And the technology we have now makes that model work better. And another thing. I think CDbaby has been a huge boom for indies.

R&R: You work with CDbaby?

Danny: Yeah, I do, and I really like them a lot. For one thing, they're extremely honest, extremely transparent. All of my business dealings with them have been way up front. They're very accountable. It's very clear what you're being paid and from where, and they pay you weekly. They don't say you need to build up an account before we start paying you. They are responsive, friendly and they have a sense of humor, which makes them great to deal with. The amazing thing about them is that just because of all those qualities, they started attracting more and more indies and more and more indies and more and more indies and they now have so many people selling with them that if an artist sells ten CDs a year, there are so many of them that it becomes a significant number. It's the whole long tail concept. The idea is--- picture a curve--- say, how many artists sell ten million records when they release one. Those people are at the top of the curve. There are only a few of those, but there are a few more who sell a million records every release, and as it goes down, there are a bunch of people who sell maybe just a hundred records a year or a thousand records a year total. That's not a lot of records. But there are so many of those people that, en masse, it adds up to a significant market. CDbaby kind of cornered the market on the long tail. That part of the curve is called the long tail. There are whole bunches of them and they're not selling all that much, but in total it's a lot.

So Apple and iTunes won't deal with an artist who's selling--- I don't know what their minimum would be. But for one thing, they won't deal with an artist directly at all unless you're the magnitude of a Radiohead or something. They deal with record labels and distributors. But even then, they aren't interested in artists who sell less than, whatever, a thousand or two thousand CDs a year. But they will deal with CDbaby because CDbaby--- if iTunes has an issue with any of the details--- say, accounting--- they have one person they can go to talk to. CDbaby is their portal to the entire indie music world. And because there are enough artists who sell through CDbaby, CDbaby can actually leverage a pretty good deal with people like iTunes, Rhapsody and other online music services. Because they have so many of these artists, they can actually leverage the same kind of deal that a major label can with their artists. So myself, even as just a drop in the bucket for iTunes, I make the same amount per song as the Rolling Stones do. That is totally due to the fact that CDbaby has that kind of leverage to do that now.

R&R: So that's one of the positives about signing with CDbaby?

Danny: You don't have to sign with them. They're not exclusive. If you're interested in working with them, they sign you up for a nominal signup fee just to set up the page. They give the artists the best split from sales for anyplace online that I've found.

R&R: This whole concept of selling things through CDbaby smacks of commune, does it not? I mean, like you were talking about with Twin Oaks and the farm?

Danny: It's similar in the sense that there is an economy of scale. If you get enough little people together, they make an entity big enough that it's worth the big boys' time to deal with you.

R&R: So basically what you are doing is using them to physically get your product out there.

Danny: They're there for two things. One, they're a retail front. Unless you have a shopping cart system on your own website and a fulfillment system where someone can order from anywhere in the world and you can process their credit card and ship the CD out to them the next day... If you don't want to deal with that, you can hire CDbaby to sort of be your retail front. It's like putting things on consignment. You send them CDs for free and as they sell them they send you the money. But they deal with all of the processing and they deal with all of the shipping and they deal with all of the angry customers.

They started as a retail front. Once they realized that they had this huge catalogue of artists signed up with them, they went into the business of being a digital distributor, so that when eMusic opened up and as iTunes opened up... They wanted as much music as possible, yet they don't have the human resources to deal with each individual artist. I don't know how many, but it's something like three hundred thousand artists on CDbaby. That would swamp iTunes. But CDbaby already has them in their system. They already have the data, they have all of the songs coded, so they can distribute that material to iTunes. They can distribute it to eMusic. There is a place on your CDbaby music page which asks which of the music services you would like to distribute your music.

R&R: So if you didn't want to sell it as an mp3, you could just check only physical product?

Danny: Yeah. You can opt out. Or you can say I want to sell through iTunes but I don't want to sell through Rhapsody or vice-versa. In that sense, they act just like any other distributor. They want to know where you want it placed and they get it there.

R&R: Does eMusic have an option to say no?

Danny: eMusic can sell whatever they want to, but it's in their interest to sell your music. It costs them nothing to store your music there and on the off-chance that someone wants to buy it someday, they might as well just have it. Plus, then they can say they have sixty million songs on their system. Thirty million of them might be songs that no one has ever listened to, but they can still claim to have this huge library. Disc space costs nothing and they aren't charged anything until someone buys something. What happens is that if someone goes to iTunes and buys a 99 cent song, Apple takes the first 33 cents, CDbaby takes like seven cents or something like that for their services as a distributor (which is much, much less than any other distributor would take), and I get the rest.

R&R: Are your mp3 sales significant?

Danny: Pretty good, I guess. I'd say about a third of my sales are mp3, but it's hard to say. A third of the sales directly from CDbaby are mp3 sales. Then, every quarter or so, iTunes will send an accounting. That's the nice thing about dealing with a distributor like CDbaby. I don't have to hound iTunes to get paid and I don't have to look over their accounting to make sure they did everything right. CDbaby does all that stuff and just forwards the check to me.

Which is what I'm saying. The infrastructure now exists for indies. That's a lot of business I am able to do with very little time expended. I just have to set up my stuff on CDbaby and tell them to go to town and all of a sudden I have international distribution of my material.

R&R: What percentage of your business would be going through CDbaby, a rough estimate?

Danny: Of the online stuff, I'd say maybe 90 percent. I still sell more at shows than anywhere else, but CDbaby is the main avenue through which people find my music online. The exception being that Waterbug has a physical distribution deal and what they handle gets sent to Amazon and outlets like that--- some of the other online retailers which deal in physical product. I try to minimize those sales as much as possible because they are much worse deals, both for myself and the customer.

R&R: You mean in terms of the amount of money you get?

Danny: Yeah. If I sell something through Amazon, I'm probably making three dollars, ultimately, by the time the money makes its way back to me. When I make a sale through CDbaby, I make ten dollars. And it is probably at least as cheap for the person buying... probably a little cheaper.

R&R: Just looking at the pure numbers, you're talking about hundreds of thousands to millions of songs available online, and I suppose that if you go back to the fifties and beyond, you're talking millions and millions.

Danny: Yeah. I think iTunes claims to have sixty million songs right now.

R&R: Do you think that maybe just the mere volume of that is stopping the music industry from regaining its feet? And I'm not talking about the major label music industry, but the actual music industry. All of it. From the guy who plays down the street at the coffeehouse to the major star.

Danny: Well, the whole model used to be based upon all of these people doing work and all of that work paying off when people sold records. That was the business model. That's where the revenue stream came from. They used to promote tours as loss leaders, as traveling advertising campaigns which would drive publicity and promotions until eventually it would come back as record sales. So the whole music infrastructure was dependent upon album sales. It's not strictly that way anymore.

R&R: You say you have known Devon Sproule for some time now? What is it about her that makes people respond?

Danny: It's funny. I have a hard time separating the person from the music after awhile. Once I know them and know their music well--- I always find that it's the same sort of attraction. Devon is extremely vivacious and very bubbly. She is obviously really sharp and intelligent and analytical, but she also doesn't take herself too seriously and is very fun-loving, so there is this nice kind of dichotomy or at least balance.

She has a very strong musical background. Her dad was into The Beatles and Tin Pan Alley stuff along with the standards, so she is always challenging herself musically and melodically and chordally. Her music comes out challenging and somewhat pushing the threshold, so most people really admire her moving up and down the neck of the guitar with all of these cool and jazzy chords. Her personality is so accessible and the songs and the themes within the songs are accessible. And people love that she is young and has a lot of energy. The music she plays is more rooted and thus appeals to the more older folks who relate to it musically a bit without realizing that it makes them feel kind of hip. And the younger folks relate to her because she is a lot like them, or seems to be. She's not a stodgy folksinger and she's really attractive. She's really cute.

R&R: From the pictures I've seen of her, she looks very personable.

Danny: She is. She's extremely personable, and it's not like it's stage presence. She is genuinely personable. She's the kind of person who is very engaged with you when you sit down and talk, and she's like that with everybody she meets.

R&R: What about Joia Wood?

Danny: I've been trying to kick Joia in the ass for about eight years. She's always on the verge of recording her own stuff. She's one of these people who overthinks her own stuff before she tries it and, as a result, she doesn't end up putting herself out there as much as she should be, musically speaking. But she's making baby steps towards that. She finally made a live record last year (Live at the Gravity Lounge) which is really good, and has started putting a band together. That was a big step. And she's starting to do a few shows out of town.

My own experience with her has been as a harmony vocalist. I was in town only a month or two before I met her. We were at a party where people were just passing guitars around and she sang something with me. I forget what it was, but by the time the last chorus came around, she was singing on it. I invited her to sing with me at a show and after that, we got together whenever we could.

R&R: The voices matched well?

Danny: She has an amazing voice. She can do a lot of different things with it. She can do this really delicate, breathy stuff. She can totally rock out. She can do this soulful kind of Blue Note thing. She can do this pure country thing. She is extremely versatile. I've always had a strong sense of harmony and where I wanted the vibe to be, but I don't always know what the notes are I'm looking for. She hears them right off the bat. She'll try something and I'll say, no, try something higher or something more monotone which doesn't move around quite as much. Then she'll try something different. It's pretty amazing how easily she comes up with harmonies.

R&R: How did she come up with her part on Leaves Are Burning? You said that you turned the mike up all the way and left the room, but you had to have worked on that before the sessions.

Danny: Really, not at all. One of the things I like about Joia is that I can talk to her in sort of abstract terms. Like I'll talk about what the vibe is I'm looking for on a song, or what I'm trying to create emotionally--- in those terms and not musical terms. And she understands where I'm coming from. We have a really nice communication rapport. On Leaves Are Burning, we'd already added the sort of feed-backy guitars and I told her that we just wanted a weaving, wailing part that somehow builds to some sort of madness and then a release from that at the end. We talked in exactly those kinds of terms. She was very self-conscious. If you were to hear those parts solo, without all of the music going on around them, they sound pretty primal and freaky and creepy and cool. But she was a little self-conscious having us there and thought she could cut loose a little more if we weren't there. And she wanted to do a bunch of really quiet things as well and we liked how it sounded when she did that, but she stood five feet away from the mike, so in order to capture that, we had to gain on everything, up as high as it would go. We were creeping out and she had the headphones on so it wouldn't explode in her ears. She did one pass, we came back and listened and talked about more of this kind of thing and less of that kind of thing and this is totally great. If there was something she did that we liked, we'd say how about if you try this when we get to this part, where you maybe hold out some long, screeching note throughout the whole thing. We basically refined what we were looking for and then would just totally go to town. We'd hit record again, told her to do three more, and snuck out. Then we picked through the material we had at that point.

R&R: How did she feel about it when she was done?

Danny: That's a good question. I don't know that I ever asked her about it after we put it all together. We pulled different parts from different sections and did a lot of processing on it to make some of it weirder and some of it less weird. I know that she thought there was a lot of cool stuff in there when she was done. But I don't know that we ever talked about it after it was put together. I talked to her about the whole record, but not specifically that song. We've done some other pretty avant-garde things in the past. There was a song called Sometimes a Friend from Enjoying the Fall which has her doing some pretty out-there stuff, too. She's a good sport. She's always willing to try different things and see what happens.

R&R: What about Paul Curreri?

Danny: Paul is a fascinating and wonderful character. He's sharp, extremely creative. Almost too creative for his own good.

R&R: What does that mean?

Danny: He went to the Rhode Island School of Design and I think he's got a bit of an art school mentality in that he's always got to be challenging his own creativity, pushing the boundaries to keep things new and interesting to him.

R&R: You mean like The Velvet Rut?

Danny: Yeah. Exactly. That one became an organic process of pushing the creative envelope for him, I think. And like anything that treads new ground, it's risky and it's exciting, and the best of it, when it's successful, becomes something that is actually artistically important and not just artistically pleasing. I think that is something Paul is always striving for, which I find really admirable. Working with him on the production of Little Grey Sheep, he would have some absolutely brilliant and mind-opening ideas. And he would have some crackpot ideas on occasion. Like on Drawing Board, he went through and detuned every fourth space note to some dissonant harmony because he thought it was a really cool idea, and it sounded like crap, you know? But in his head he is always playing with ideas like that, and some of the things he came up with were great, were brilliant, in fact. I mean, some of the best moments on the record were Paul's ideas. At his worst, he isn't always the most judicious about which idea to go with. Sometimes he needs to concentrate on just making this pretty rather than interesting. I think it would serve him better, at times.

Danny: Yeah. Exactly. That one became an organic process of pushing the creative envelope for him, I think. And like anything that treads new ground, it's risky and it's exciting, and the best of it, when it's successful, becomes something that is actually artistically important and not just artistically pleasing. I think that is something Paul is always striving for, which I find really admirable. Working with him on the production of Little Grey Sheep, he would have some absolutely brilliant and mind-opening ideas. And he would have some crackpot ideas on occasion. Like on Drawing Board, he went through and detuned every fourth space note to some dissonant harmony because he thought it was a really cool idea, and it sounded like crap, you know? But in his head he is always playing with ideas like that, and some of the things he came up with were great, were brilliant, in fact. I mean, some of the best moments on the record were Paul's ideas. At his worst, he isn't always the most judicious about which idea to go with. Sometimes he needs to concentrate on just making this pretty rather than interesting. I think it would serve him better, at times.

R&R: Was he hard to work with as a producer?

Danny: He's one of my best friends, so in that sense it was really easy to work with him because we communicate very well. We definitely butted heads around some issues. He thought I was being too stodgy with a lot of the artistic decisions and I thought he was being a little too wild with some of his.

R&R: Was that a good thing?

Danny: Oh, yeah. But it didn't make it easy all the time. There were moments when he was ready to throw me out on the highway and there were moments of frustration for me as well. Ultimately, though, I think it was a good thing.

As for Paul's own stuff, at its best, his music is ingenuous. At its worst, it can maybe a a little inaccessible for people? Like there is just too much going on in it for people to really get a handle on?

R&R: Ever talk with him about it?

Danny: Yeah.

R&R: And?

Danny: Ultimately, we all have to follow our own artistic inspiration and his is to push the boundaries and to make music that he finds interesting.

We've played lots of shows together. They have a nice energy to them because we just end up onstage as good friends. I think that comes across. It's good to see him and play with him and we give each other a lot of shit onstage and that seems to come across as funny.

R&R: What about Jeff Romano? The only thing that I know about Romano, outside of the fact that he was part of Nickeltown, is the production job he did on Devon's latest album.

Danny: Jeff has done a lot of production for singer/songwriters out of Charlottesville. He has a nice pro studio, small and affordable. Musically, his main thing has been Nickeltown, though they have been on hiatus since Browning Porter, the other half of Nickeltown, had a baby. As a duo, those two were great and very entertaining. Jeff did all this really fancy intricate finger-style guitar stuff and Browning--- well, Browning is more of a poet and a writer, but he writes very funny songs. Very clever, complex songs. The two blended very well. But Jeff has lately been most involved in either engineering or producing.

R&R: So Jeff has been a pretty key guy as far as working with local musicians?

Danny: Yeah. There are two or three main people who have recorded most of the acoustic stuff in that area. He is the most prominent among the singer/songwriters. He's just a good guy. He is another one of the guys who fell in with my group of friends. We admire one another artistically, but we are all, first and foremost, friends. I think Jeff worked on two of Paul's first three albums.

R&R: Keith Morris?

Danny: Keith was the first person to review my first record. He was writing for the Charlottesville Daily Progress. I gave the paper a copy of the album for review and to promote the CD release party that was coming up and Keith wrote this really nice review. I wrote him a thank you and he asked me if I wanted to get together and talk music, so we did and totally hit it off. He's really funny. He likes to stir things up and we love him for it.

He had always been kind of a closet picker and I don't know about encyclopedic, but he knows a lot about music. He is very well-versed in where the music is coming from and where it has come from at various points. We never really thought of him so much as a player himself, but he evidently was doing these late-night four-track recordings down in the basement. At some point, a couple of years ago, he decided to take one of the four-track recordings over to Jeff and use the guitar and vocal parts as the core of a bigger production. That is what Songs From Candyapolis grew out of.

R&R: Jan Smith?

Danny: Jan is great. She moved to town just after Paul. In fact, they moved to town within six months of one another. To me, Jan writes very elegant, cohesive songs, kind of like Gillian Welch. Not necessarily stylistically, but to me Welch writes perfectly contained songs and that is how Jan's songs sound to me. She has a velvety voice and is really unassuming and has a very unpretentious stage presence.

R&R: Brady Earnhart?

Danny: Brady is the godfather of the whole Charlottesville thing in that he was already playing out and had a record when everyone else hit town. Him and Nickeltown had been going for quite awhile. Brady was kind of the resident poet. He was very crafted and literary (he is a professor of English Lit--- that's his day job), so his stuff comes off more literate. He teaches in Fredericksburg, which is maybe an hour away from Charlottesville.

R&R: When he was contacted, he said that he was not in the same vein as you guys, that he was much lighter.

Danny: Well, he's always skirting attention. I think he raised the bar for a lot of the songwriters in Charlottesville who were coming up back then. When you're still learning, you're always challenging yourself and comparing yourself to whatever other people are doing and Brady's songs were always a little bit smarter. He obviously had spent more time on his songs, crafting his words more particularly than maybe you had, and I think he had a big influence on a lot of us. And again, he was a good friend who we hung out with a lot. He was another part of our culture.

R&R: The Hackensaw Boys?

Danny: They weren't exactly in our circle of friends, but they were acquaintances and friends from around town. They grew out of a scene. There was this place called the Blue Moon Diner, which was this little hippie diner in town. Several of them worked there as line cooks or handymen or whatever. It started one summer? Every Friday, the Hackensaw Boys played there. It was a tiny little place. Jam-packed you could get maybe thirty people in that place. It was tight, sweaty, cheap beer, and the guys took up half of the space because at the time, there was like nine of them. Have you ever heard the Hackensaw Boys? They are kind of like an old medicine show. Kind of that high energy jug band/string band, rooted in bluegrass and Appalachian Mountain music, lots of hollerin' and stompin' and harmonies. Their whole thing was just to come out every Friday and have fun. They were a totally great theme band. And that place was hopping! You couldn't go to a Hackensaw Boys' show and not come away invigorated. I don't think they even made money from those shows.

At the time, they had three main songwriters who were really good in their own ways because they brought different things to the table. Robby St. Ours to me was the best of them. He's great.

They took off as soon as the owner of the Blue Moon Diner decided that these guys had something going on, and he was going with them. He spent the next summer trying to promote them. He got them some big thing opening for Cake at some summer festival. Cake hit it off with them personally and really liked what they were doing musically and invited them to do a whole national tour with them. That really kicked things off. They were all of a sudden playing to big groups of people. They did a whole tour with Modest Mouse, that whole tour with Cake.

R&R: Back to you. Can you explain the difference between Parables and Primes and Little Grey Sheep?

Danny: The attitude going in was different, as were the songs. The Parables songs I took a lot more seriously. I think they are more serious songs, actually. The ones on Little Grey Sheep mean a lot to me personally--- they'd come out of personal situations--- but I didn't think of them so much in an artistic sense, like presenting them to the world in a particular way.

R&R: That's the opposite of what I would have thought. I would have thought that Little Grey Sheep would have been the one you considered more art. Admittedly, Parables is much more rooted in folk. You can hear the influences from track to track. After hearing Little Grey Sheep, though, it's a hard step back. It almost sounds as if you're taking a step back into early British folk on some of the Parables tracks, whereas on Little Grey Sheep, your songs are more emotive and out front. Parables seems a much more structured kind of thing.

Danny: And there was a lot more narrative and more abstract feel whereas Little Grey Sheep was a lot more first person. And those, you treat differently, you know?

R&R: You do, and maybe that's the hard part. I think if I'd heard Parables when it first came out and then heard Little Grey Sheep, I might have seen the step more clearly. But going back...? I've only heard Parables three times now and I'm not really sure. But there are always reasons you do the things you do, right? When you went into the studio to do Parables, was it completely mapped out?

Danny: No. They're never all the way mapped out. You have notions of what you're going to try to do with things, but the process itself is an organic one.

R&R: Maybe that's the difference that I hear when I listen to each. On Parables, each track sounds very mapped out, very clear and precise. Little Grey Sheep sounds more open and jumping from place to place. Maybe it was my personal involvement in each song.

Danny: Maybe. And sometimes I think the process works a little differently. Sometimes it works a little better and sometimes it doesn't. I think I was willing to leave a few more rough edges on Little Grey Sheep than I was on Parables, just because I didn't take it as seriously. Some of those rough edges might have been a good thing. I think of each album as being somewhat different, but not extremely so. You might want to visit my web page (www.dannyschmidt.com) and click on Parables. It has a song-by-song commentary.

R&R: So you did the same thing there that you did with Little Grey Sheep? The commentary thing?

Danny: Yes. I think it was a little less elaborate, but Parables was the album which gave me the idea for doing that. That might help you to understand, a window to some of the tunes.

R&R: That is a very good thing, by the way. When I read the commentary on the tracks of Little Grey Sheep, I was amazed by the step by step moves from song to song. You always wonder why a song is a certain way or how much of it is you as a listener and how much of it is them as a composer/performer. I get songs wrong a lot. A prime example with you, of course, is Leaves Are Burning. After hearing it and reading your comments about health problems, I was sure it was lung cancer. That shows you how wrong I can be.

Danny: But you were pretty close.

Before we lose track, let me throw a few more names at you. They were not part of our tight circle, but they were certainly big players in the Charlottesville songwriter scene. Terri Allard, who had been doing it all several years before we got there. Shannon Worrell, who sang backup with Dave Matthews on a few things--- she was one of the ones, along with Terri, who were doing it big when all the rest of us hit town. Corey Harris, a blues player, who was one of the old guard. And there was the oldest of the old guard, John McCutcheon. None of us knew him or hung out with him, but if you're going to write something about songwriting in Charlottesville, you can't do it without at least mentioning him. And, these days, Jesse Winchester and Ellis Paul. They recently moved to Charlottesville and though they were not part of the scene when I was there, they are there now.

Thus, we left Danny amidst his long journey to Dallas, pedal-to-the-metal as they say down South though Danny seems more the type to lay back and cruise. Only later, reading through the transcription, did it become clear how well-stated were his comments. Thus, an interview instead of a less-succinct view of Danny Schmidt, musician and human being, in the form of an article.

It is largely because of him that we have taken a personal interest in Charlottesville and its musical inhabitants. It is because of him that we have decided to make the Charlottesville story open-ended, easily accomplished on the Net, so that we can fill the holes as we go. Truth be told, Charlottesville could have no better champion. Austin may be where his family lives, but it is clear that Charlottesville VA is his musical home.